According to the 2015 census, there are currently more than 350 languages – including 150 Native American languages – being spoken across the U.S. Often referred to as a "melting pot" of cultures, the presence of so many dialects in America stands as a reminder that there's no single definition of what it means to be an American.

Critics also suggest we've become less tolerant of our multiracial democracy than ever before, and a new brand of nationalism has been taking root in our politics and discourse. Instead of celebrating the things that help make people who live in the U.S. different, some have started to see them as a cause for concern or protest.

In 2019, what's it like to live next door to someone who doesn't look or act like you and that may have a very different view of the world? Considering you don't have a lot of control over who your neighbors are, how would you feel if an ardent Trump supporter moved in next door? A convicted felon? Someone who doesn't speak English? A gay couple? For a closer look at who makes Americans feel unsafe, we surveyed over 1,000 people about who they wouldn't choose to live next door to. Here's what we uncovered.

Uncomfortable Community Vibes

.jpg)

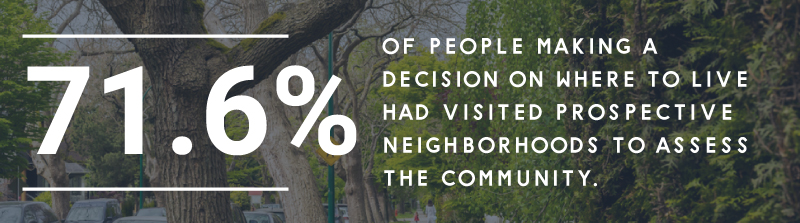

When you're in the process of moving or buying a home, it's not uncommon for a real estate agent to stress "location, location, location" as one of the most important factors to consider. As much as your home's proximity to work or school is relevant to where you want to live, so is the safety of any potential neighborhood. Without firsthand experience in the area, there are plenty of ways to gauge its safety, including looking at local crime statistics, watching for a constant police presence, or taking note of abandoned buildings.

When asked which types of neighbors would make them feel unsafe, a vast majority of people identified people with a criminal record. While 80% of Americans said they'd feel unsafe living next to a sex offender, another 70% said the same for anyone arrested for violent charges, and 49% identified those arrested on drug charges. No matter where you live, the National Sex Offender Public Website will identify if there's a sex offender in your neighborhood, though you may not be automatically notified by the city or state. While you can't legally harass or discriminate against someone on the registry, there are no laws prohibiting neighbors from sharing information with each other when a sex offender moves into the area.

Other concerns included living next to someone with a confederate flag in their yard (38%), neighbors who rent their homes on Airbnb (27%), and avid supporters of Donald Trump (26%).

Demanding Certain Dialects

.jpg)

English may be the most commonly spoken language in the United States – and even in many places around the world – but the U.S. has no official language, nor does it require citizens (or those applying for citizenship) to speak fluent English. Instead, an applicant seeking naturalization is only required to demonstrate the ability to read, write, speak, and understand "words in ordinary usage," and it's even possible to receive an exemption from these stipulations.

Overwhelmingly, we found older respondents and those with conservative political beliefs were the most likely to be uncomfortable living next to someone who didn't speak English. Compared to 34% of baby boomers, we found roughly 26% of Generation X respondents and 21% of millennials struggled with the idea of having a language barrier between themselves and their neighbors.

We also found white (28%) and black or African American (27%) respondents had the strongest biases against living next to a non-English speaker. And while just 16% of people with left-leaning political beliefs felt uneasy living near someone who might not speak their language, 45% of right-leaning respondents echoed the sentiment.

Not in My Neighborhood

.jpg)

A symbol of great historical significance, almost no image in the United States is perhaps as controversial as the Confederate flag. According to some, the Confederate flag represents a painful and violent part of American history that's deeply rooted in both war and racism. For others, the Confederate flag is a symbol of Southern pride, and even potentially a symbol of defiance to liberalism.

As revealed by our survey, many Americans would choose not to move next door to someone who had a Confederate flag in their yard. Led by 60% of millennials and 57% of Generation X respondents, 46% of baby boomers agreed they would avoid living next to someone with a Confederate flag on display.

The men and women we surveyed were nearly split – 58% and 56%, respectively – on the safety of living next to someone with the Confederate flag in their yard, though people of different political persuasions were deeply divided on the issue. Compared to 73% of respondents who identified as left-leaning politically, just 38% of conservatives we surveyed would avoid living next to someone flying a Confederate flag.

Despite reports that neighborhood-level diversity is more common than ever across American suburbs, it's important to recognize that even among the most diverse communities, divisions of race and power are still prevalent. While the block you live on may have a mix of races or ethnicities, you may discover that the social institutions (including churches, restaurants, and hair salons) remain deliberately segregated in what is referred to by some as "microsegregation."

What We Know About Our Neighbors

.jpg)

People we polled identified a number of different scenarios that would make them feel uncomfortable about their neighbors. Learning they were an enthusiastic supporter of Donald Trump, lived a polyamorous lifestyle, or had a criminal record were typical causes for concern. Still, it's entirely possible that any one of those things could be happening in your neighborhood and you would never know it. Despite what life might have been like 30 years ago, studies suggest Americans today know less and less about the people in their communities.

Ninety percent of baby boomers said they feel accepted by their neighbors, a likelihood that decreased among younger homeowners, and was followed by those who leaned right on the political spectrum (88%).

Building Stronger Communities

Over the course of our survey, we found many homeowners had very strong opinions about the kind of people they would want to call their neighbors. While the safety concerns of living next to someone with a criminal record were often the chief complaint, we found politics were another very strong dividing factor.

For most people, the presence of the Confederate flag was very polarizing, and many Americans would choose to not live in an area where this flag was present. Still, we also found a majority of people didn't know much (or anything) about the people living next door to them. In many cases, we found more than half of Americans didn't even know the names of their next-door neighbors, and some demographics (including biracial, Asian, and black or African American respondents) were far less likely to feel accepted in their own communities.

Sources

- https://www.theodysseyonline.com/is-america-actually-melting-pot

- https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2019/07/send-her-back-battle-will-define-us-forever/594307/

- https://www.aetv.com/real-crime/what-can-you-do-if-a-registered-sex-offender-moves-into-your-neighborhood

- https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/what-is-the-official-language-of-the-united-states.html

- https://www.popsugar.com/news/Do-You-Have-Speak-English-Become-American-Citizen-43828824

- https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2018/aug/06/pride-and-prejudice-the-americans-who-fly-the-confederate-flag

- http://www.slate.com/articles/business/metropolis/2017/07/why_even_diverse_neighborhoods_remain_segregated_by_race.html

- https://qz.com/916801/americans-dont-know-their-neighbors-anymore-and-thats-bad-for-the-future-of-democracy/

- https://lgbtqia.ucdavis.edu/educated/glossary

Methodology and Limitations

The data presented in the above study were gathered through the use of the Amazon Mechanical Turk service as well as Prolific through a survey given to participants. In total, there were 1,002 respondents surveyed, with 553 women, 433 men, and 16 people who did not specify. 214 of the respondents were baby boomers, 276 were from Generation X, 462 were millennials, and 50 came from generations outside those. The study included 769 white respondents, 54 Asian or Asian-American respondents, 73 black or African American respondents, 61 Hispanic or Latino respondents, 36 multiracial/biracial respondents, three American Indian or Alaska Native respondents, and three Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander respondents.

All data presented in the above study rely on self-report, and self-reported data can come with issues like telescoping and exaggeration. In order to ensure respondents were not answering randomly, an attention check was used. Respondents were presented with a question asking if they belived they were a part of the LGBTQIA community, with the letters standing for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, and Asexual provided with the question.

Fair Use Statement

Want to share the results of this study with your digital neighbors? Don't worry, you won't have to learn all of their names first. We encourage the distribution of this article and all related contents for any noncommercial use. We simply request that you include a link back to this page to help support our community of contributors.